This site started in 2006 as a blog and it never lost its genesis, but it is now much more than that. It is a record of what I have seen in the context of Digital Communication since there was no Facebook and talking about the internet made our interlocutor roll his eyes.

Web 2.0 came along, the first social media platforms, the first social and economic phenomena driven by the digital environment. There were flash mobs and companies that shut down as a result of public relations crises. Portugal was no exception, the Web caused the collapse of the Ensitel brand.

Companies woke up quickly and resorted to marketing agencies. I worked in some as Social Media Manager, I took part in communication strategies where social media always orbited the traditional media or was the only element of the proposal. Interestingly, in the early years, they were never at the center. They became a central element when brands committed to training marketers and hiring specifically for digital communication.

Fifteen years ago, it made sense to call this site a blog, entitled “Online Public Relations”. Today, corporate communication is essentially digital, and I already introduce myself as a Communications Strategist without having to explain what “being Digital” means.

Meanwhile, the social media landscape has broken down. Yahoo! has lost its strength as a search engine; Facebook has expanded its app and ad marketplace offerings; social media is born and dies slower. Nobody remembers Haiku, Vinel, or MySpace anymore.

And, in between, the era of startups began. WebSummit grew to fill halls with more attendees than a football stadium. After the emergence of online services like Spotify or Netflix, Uber appeared, and companies whose business model establishes the bridge between digital and analog.

And where are we?

In this historical briefing, we are left with the feeling that the Human being is just an interface capable of making money and time flow in these digital channels. Privatized communication channels have dominated us.

Marketing had learned to use statistics as a cornerstone, basing itself on numbers in digital channels, and trembled when “General Data Protection Regulation” first came long.

Democratic values have not withstood Facebook’s algorithm, neither has our mental health.

Misinformation widespread by algorithms, which value interaction without taking into account the quality of information, has become a pandemic with no possible vaccine at sight.

How has this happened to us? The answer is not very difficult.

Companies have always aimed to profit, and this is what they did in a digital communication whose context had no ethics, deontology, or morals.

We have always been instinctively social and used social media as escapism and optimization of the time we spend on public transportation. In the hustle and bustle of everyday life, we want to find empathy and contact people who think and feel like us. We want to find people like us and we are willing to spend hours doing swiping just to find them.

Without regulation or restraint, we have reached saturation point. There are too many social media platforms, too many notifications, too many needs. Apple has reacted with new options for controlling notifications and even Google engineers have waved the flag of individual protection in the face of these relentless pressures.

Bots, the Digital Agents

The social media platforms that have managed to hang on for the last ten years are not going away. There is no rebranding capable of clearing Facebook’s record, even if that is Meta’s goal. These companies will continue to want to make a profit and will want to tread the boundary of reasonableness until someone tells them to stop.

We can claim that the invasion has already begun, because the action of digital channels is not only limited to computers and phones. Alexa is in the living room, Siri is always by our side, Google Assistant knows our favorite restaurant.

From my perspective, this is all still the stuff of early adopters. I know few people who regularly use Siri or chat with Alexa. These virtual assistants help us with sporadic information or simple tasks. “Remind me that I need to buy fruit when I get to the grocery store”.

“Turn on the living room lights.”

It will happen eventually, but we are not yet in a true artificial intelligence within reach of anyone. And, even if we were, this is a maturing technology. For Elon Musk, artificial intelligence can be something that is part of us and we of it.

While the zenith of artificial intelligence does not arrive, more digital assistants may emerge and offer us increasing value. They may be mechanisms to save us time by solving boring tasks, or they may be a second brain.

The world of digital assistants

For simple tasks, the offer keeps getting bigger. From the famous IFTTT, which observes what happens online to perform predefined tasks, to Zapier. The latter allows you to create complex streams of actions for people and companies to automate work and communication processes.

Aurora is an excellent example of an app that acts as your digital assistant in the face of a concrete and complex problem.

Aurora is a baby and child expert, always available to chat with you and help you learn the mysteries of sleep of the little ones or clarify questions about breastfeeding. Through Facebook Messenger, Aurora is always online for you.

Aurora helps families care for their youngest, step by step. It teaches parents the signs that deserve attention, while sharing proven tips for getting children into a healthier sleep rhythm.

We want digital assistants like Aurora, with a positive impact on our quality of life. We want technology to be a source of energy, not a psychological drain like the one caused by social media.

Companies have invested time and money to build chatbots that end up becoming just another annoying notification. These digital assistants are waiting for us on websites and talk to us as soon as they detect the first sign of inertia.

No, I don’t want to subscribe to the newsletter. Thanks, but I don’t need help, I’m reading the website.

But I do want a digital assistant to organize my invoices, identify important emails, or search stuff for me. I also don’t want it living on another company’s server or the information it stores about me to be used to manipulate me.

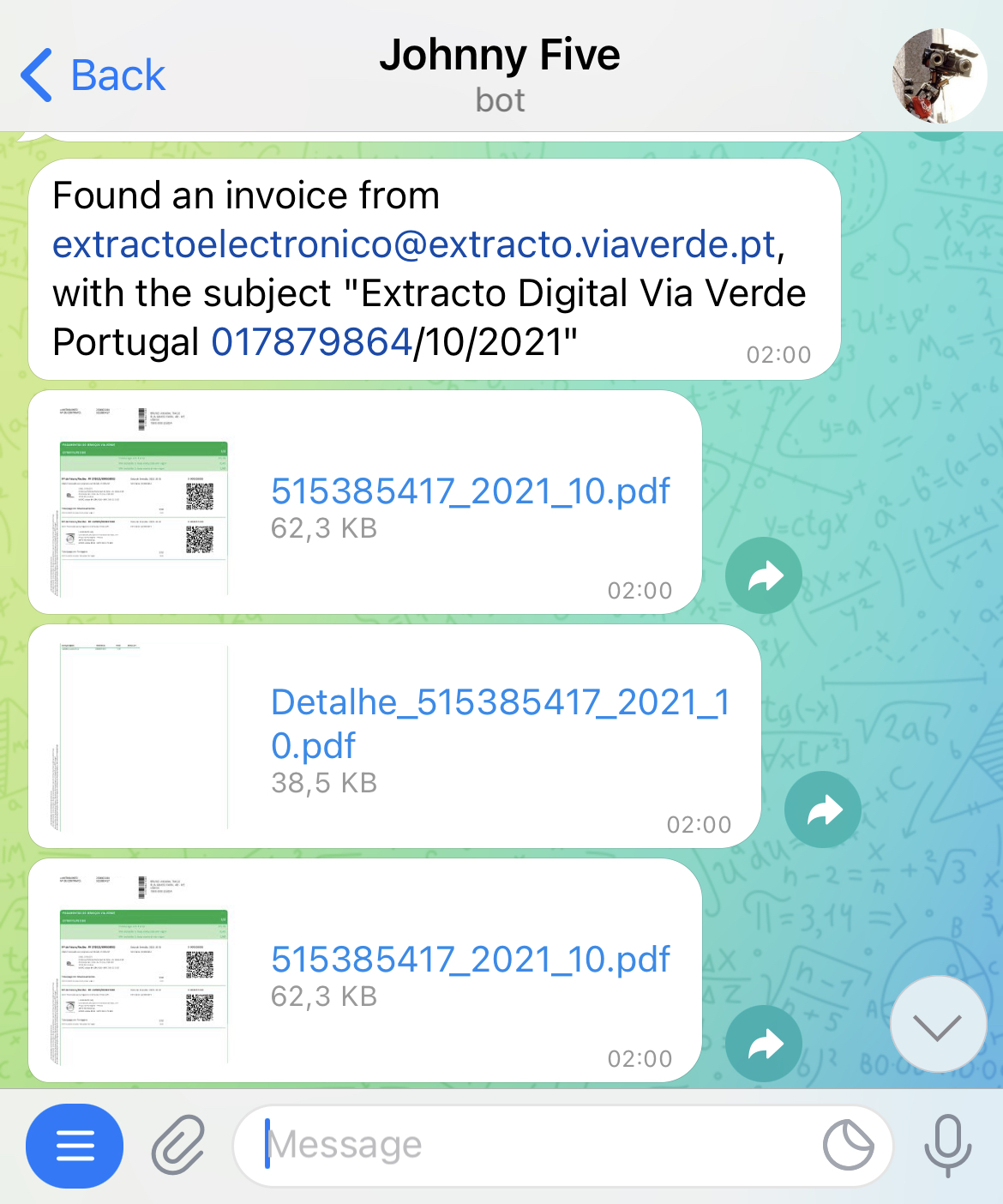

Johnny Five is a digital assistant that I have programmed to simplify small everyday hassles. I think that a being like Johnny would be useful to many and, as time moves on, we will start to notice breakthroughs in this field. But, until then, I feel that companies are lost in how to use digital assistants in their communication, whether chatbots or similar.

They are focused on profiting and interrupting our concentration just to try to sell us something. Elsewhere behind the scenes, there are wars of other bots and digital assistants.

High-frequency trading (HFT) is already an old term, which translates into buying and selling stocks based on an algorithm. This allows a much faster reaction to market changes and the possibility to profit without the need for human interaction.

Until this year, this was never more than putative talk. “They know their stuff overseas…”, “Those guys know plenty about that thing…”. Those were the ones who knew about HFT and who activated these bots and digital assistants.

Today, there are bots used for all purposes, capable of shaking up entire industries. In retail, they are used to buy limited edition products. On Instagram, they allow us to inflate followers and distort the perception of importance and relevance we attach to people and content. This is what we saw in the documentary Fake Famous.

These two reasons show why digital agents are a concern for companies. If they are misused by the company, they are detrimental to the shopping experience and communication. And, without any protection against these bots, companies are at financial and reputational risk.

What can we expect?

These digital agents already have a considerable impact on the daily lives of people and businesses. We may come to adopt them naturally, just as we have adopted social media, at least as long as they fulfill their purpose without becoming toxic.

They may also naturally play a role in different parts of business communication. Besides automated contact with stakeholders, they may one day analyze interaction statistics, suggest campaigns, and some already manage them. (Programmatic Advertising)

This questions the role of communications professionals in companies and, on the other hand, requires more detailed branding work to ensure the coherence of digital communication, whether programmatic or not.

From another angle, automating these tasks allows us to communicate more humanly in digital channels. If the reporting is automated, we have more energy to analyze, contextualize and suggest qualitative changes. If the robot can check our calendar and schedule meetings, we can dedicate ourselves more to the quality of personal contact.

From a positive perspective, these digital agents will increase our quality of life. On the other side of the coin, we will have a lot of conflicts with digital agents that look at us as mere instruments for a purpose.

I believe more in the negative view, given the lack of information about artificial intelligence and its use.

Saving the best for last, Gregory MS

After Johnny Five, I devoted myself to a digital assistant with a more honorable purpose than organizing invoices, writing down tasks, and reading emails.

Gregory MS lives somewhere in France, spending its days collecting articles from Neurology, which it then analyzes to find those relevant to improving the quality of life for people with Multiple Sclerosis.

In Digital Communication, Gregory is not just a robot. It is a personality, a Brand with its branding, with a tone of voice, a purpose.

It is not an artificial intelligence, but it has a machine learning algorithm (ML), which is used to analyze the title and abstract of articles. Since this is a sensitive area, Gregory only checks 10 websites dedicated to scientific research.

To spread its work, Gregory participates on Twitter and sends weekly newsletters to subscribers.

In its permanent diligence, Gregory has already compiled over 5000 articles, and this entails several Communication and Stakeholder Management issues.

Without the participation of someone with a medical background, what validity should we attribute to these results?

While it is relevant for healthcare professionals, it is also relevant for research labs. How does a company relate to a digital assistant? What is the level of risk?

How can the information it identifies as relevant be used to support innovation in the medical field?

Should the publications where Gregory collects information support or block its research?

With its access being free and open, with a volume of a thousand people a week, this will stir questions in patients and caregivers. Can the medical community allow a digital assistant to be part of their environment? And how?

Gregory was born to serve a very specific community. Now it is important to start the dialogue about its value and how it can become an accelerator for scientific research.

In the meantime, talking to people about bots and digital assistants still makes our interlocutor roll their eyes.

Tara Winstead